Donny Robinson's Dire Dilemma

Concussions Threaten BMX Racer's Career

Donny Robinson has been racing BMX for 24 years and has suffered, by his estimation, at least 25 concussions over that span. That’s nearly one concussion for each of the thirty years he’s been alive.

Donny Robinson has been racing BMX for 24 years and has suffered, by his estimation, at least 25 concussions over that span. That’s nearly one concussion for each of the thirty years he’s been alive.

“Part of BMX racing is the crashing,” Robinson told ATLX. “We try not to do it, but ultimately it’s going to happen because it’s a contact sport.”

At 6 years old, Robinson began racing. In that initial year, he suffered his first concussion, which he describes as a “full knockout.” He recalls riding around a parking lot without a helmet that day.

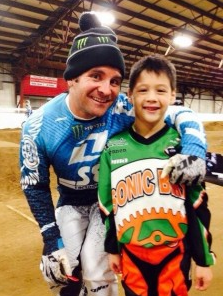

Early on, Donny quickly became known for three things. “I would be the smallest guy out there, I’d be the smallest guy trying to jump the big jumps, and I had some pretty gnarly crashes, as well.”

And he’s still the smallest guy out there as a pro, measuring in around 5-foot-4 and 150 pounds.

As a teenager, as Robinson accumulated more and more BMX experience and his talent began to coalesce, the hits started coming fast and furiously. It was between the ages of 14 and 17 that he distinctly remembers “crashing a ton.”

There was far less awareness surrounding concussions and head trauma circa 2000, however. Pediatricians and whomever else Robinson was sent to see would tell him that it’s probably not a good thing to keep hitting his head, but he was offered neither any concrete evidence nor potential consequences should it continue to happen.

Robinson would have headaches, sure, but no symptoms that he felt needed to be taken seriously. He saw himself as one of the lucky ones, only having broken a couple bones his entire life.

There was a running joke between dad and son that as long as Donny landed on his head, he would turn out to be all right. It was when he stuck an arm out to break his fall that he broke a thumb or wrist.

Father and son could not have been more wrong, and that has become increasingly clear to Robinson over the last three years, as public consciousness and his personal awareness have evolved considerably on the issue of concussions.

“With everybody not knowing how severe concussions were a decade ago or even two or three years ago, it was kind of something that didn’t play a part to me at all,” says Robinson. “I would crash, hit my head, and I wouldn’t really know if I got a concussion. It wasn’t until recently that we found out that you didn’t have to be knocked out to have a concussion.”

Brain trauma isn’t visibly apparent like a broken bone.

With a broken collarbone, for example, a rider would be sidelined. “It’s something that you can see and something that you have to wait to heal,” says Robinson. “But as far as the head goes, it’s really just kind of based on how you feel. You hit your head and if you can still function, then, ‘Let’s go kick butt,’ and get back out on the track again.”

Donny absolutely adores his fans, but the vast majority of them fail to grasp the grave damage he may be doing to his long-term health if he continues his racing career.

Unsurprisingly, they don’t want him to retire. “Even if I was to hint about retiring, I get feedback like, ‘No, you can’t. We still need you out there.’”

To his fans, he’s still the same old Donny – not to mention only 30 years old – so why would he even contemplate retirement?

“They look at me and they talk to me, and they watch me ride or they take a clinic with me, and Donny’s the same person,” says Robinson. “They can’t see anything different, so they’re just assuming that I’m fine.”

But, of course, Donny may not be fine, whether that becomes noticeable in the near future, the much more distant future or somewhere in between.

In 2011, while racing at the Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista, Calif., Robinson incurred what he believed to be a minor concussion.

“These athletic trainers are going through the concussion [testing] protocol, giving me these [memory and balance] tests and everything,” Robinson recalls. “I thought I did relatively well, but they ended up pulling me off the track and not letting me race again.”

He was fuming. On his way home that day, Robinson fired off a Tweet that essentially said, “I wish the doctors would stop telling me what to do. I’m willing to die for this dream.”

Looking back on his statement now, Robinson laughs. It was written in the heat of the moment, soon after doctors had prevented him from riding and from practicing his life’s passion.

He now wholeheartedly understands the value of having qualified medical professionals on hand to take care of athletes. For that reason, it infuriates Robinson that if he were not a big-time BMX racer, he would not have even been treated or told to stay off the track.

“To this day, there is still nobody at our domestic races on our national circuit that can look at kids that crash and diagnose them with a concussion or tell them to rest,” says Robinson. “And that really bugs me, because the only people that are able to get the care are us kind of Olympic athletes. It’s not until you go to the World Cups and the serious pro-level events that you get the doctors and the athletic trainers that are there that can diagnose [head injuries].

“So I’m constantly looking at these kids at these events that are not supervised, where their parents are watching them crash on their head, and they’re just sending them right back on the track.”

During the zenith of Robinson’s career, he was the No. 1 pro, a national champion and an Olympic bronze medalist. In fact, between 2005 and 2010, he barely remembers crashing at all.

In the four years since, he’s crashed often, suffering eight or nine concussions over that period. Even worse, “the majority of them have been total knockouts,” Robinson says.

“It’s now become serious enough to me where I’m like, ‘Wow. OK. Now I have all these doctors who are knowledgeable in the head trauma area, telling me never to get on my bike ever again,’” says Robinson.

Robinson has been advised to retire despite being told by “half a dozen doctors” that he is continually passing all memory and balance tests.

Fortunately, over the last few years, UCLA researchers have developed a way to detect early signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease that occurs in individuals who have suffered serious head trauma and is linked to depression and dementia. Previously, autopsies – which of course come after a person has already died – were required to diagnose the disease.

Now, with a new procedure, researchers can look for the buildup of tau proteins, which, if spotted, are a strong indicator of CTE. As brain tissue degenerates, tau proteins begin to appear.

Earlier this week, Hall of Fame running back Tony Dorsett, now 59, announced that he was diagnosed with signs of CTE after receiving PET scans from UCLA. Last year, five other former football players were tested, and all five were given the same diagnosis by UCLA researchers.

At first, when Robinson became aware of the scan and that he would probably have access to the resource, he didn’t want to do it. He just didn’t want to know.

“[It’s] just like how people have varying opinions on whether they want to know the day that they’re going to die,” says Robinson. “And really the scan could tell you, ‘Hey, in five years or in 40 years, you’re probably going to be brain dead.’” The prospects scared him.

After thinking about it nonstop, Robinson reconsidered. He came to the realization that it would be better to know so that he could prepare for the future – should there be anything to prepare for – rather than he and his family being blindsided by sudden, startling symptoms.

“We’re all complacent thinking that we’re going to live forever and most of the time we waste our day doing things that we shouldn’t or don’t need to, so after thinking about that, I was like, ‘Man, I want to know, because if I only have 10 years before my brain fades away, I want to be able to live my life as full as possible.’”

He’s sick of hearing about what may happen to him, but it’s something he knows he can’t ignore. He understands that he may be in Tony Dorsett’s shoes sooner than later, and that genuinely frightens him. He wants the chance to combat CTE if, indeed, the disease will be part of his future.

Sadly, at the age of 30, this has become “one of the most difficult times in my life,” according to Robinson, who agonizes over whether or not he should retire every day.

The dilemma is real.

If Robinson suffers concussion-related complications later in life, he’ll regret not retiring sooner, he says. On the other hand, if he retires while he’s still physically able to compete at a high level and doesn’t end up suffering from CTE symptoms, he’ll regret prematurely ending his racing career, his life’s passion. There’s also the chance in his mind that enough damage has already been done and that incurring further head trauma would only very minimally damage his future more than it already has.

Robinson has accomplished a great deal in his time as a BMX racer; medaling at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, appearing on national talk shows and McDonald’s cups and getting sponsored by Hershey’s, among other accomplishments. Still, he wants to achieve more, yearning for another Olympic appearance and world title.

He goes back and forth.

“There’s hardly anything in life that I love more than racing my bicycle,” says Robinson. “But at the end of the day, I would rather be able to function properly, remember my wife, my family, my friends, have coherent conversations.”

At the same time, as with many professional athletes, much of Robinson’s self-worth is tied to the sport.

“It’s not completely true, but I feel that my worth comes from BMX and racing and inspiring kids and helping them to have a chance in this sport like I have,” says Robinson.

Robinson has spoken with retired athletes who have already begun suffering symptoms of CTE – they had eight or fewer diagnosed concussions, let alone his suspected 25 – and they preach to him to think long and hard about retirement.

There’s no immediate timetable for Robinson’s agonizing decision to be made, but the lifelong BMX rider is naturally itching to get back on the track when the season begins in January. It’s what he’s done his entire life, and at this point, he’s just not sure he can give it all up.

Originally published by the ATLX Channel (link no longer active). This story was awarded third-place prize by the LA Press Club for the 2014 Online Sports Feature/News/Commentary category.